Perception vs Perspective

When I played rugby, I was a Scrumhalf. That role demanded quick decisions, sharp awareness, and constant communication-all within a narrow window. My world was the ruck, the Flyhalf, and anything that moved inside hat circle. Every play started through me. The timing of the ruck, the tempo of our offense-it all flowed through my hands, my eyes, and my voice. In that position, you don’t have time to look at the entire battlefield. You live in the now.

Seeing Through Self

Perception is the story our brain tells us in the moment. It’s based on our personal experiences, our mood, and even our physical state. It’s internal. It’s fast. It’s protective.

Athletes know this feeling well. You miss a shot or turn the ball over and immediately your mind shouts, “You’re messing everything up!” That’s perception-a self-centered, emotionally charged interpretation that’s happening in real time.

Perception is shaped by our upbringing, trauma, coaching experiences, even the last conversation we had before the game. In psychology, we often call these cognitive filters or schemas. And the brain’s default isn’t truth-it’s survival. We interpret the world based on what we feel and assume.

A parent might see a coach subbing out their child and instantly perceive it as punishment or dislike. A player might hear a teammate sigh and assume it’s directed at them.

It’s not about what is, it’s about what we think it is. And that’s where perception becomes powerful-or dangerous.

Athletes know this feeling well. You miss a shot or turn the ball over and immediately your mind shouts, “You’re messing everything up!” That’s perception-a self-centered, emotionally charged interpretation that’s happening in real time.

Perception is shaped by our upbringing, trauma, coaching experiences, even the last conversation we had before the game. In psychology, we often call these cognitive filters or schemas. And the brain’s default isn’t truth-it’s survival. We interpret the world based on what we feel and assume.

A parent might see a coach subbing out their child and instantly perceive it as punishment or dislike. A player might hear a teammate sigh and assume it’s directed at them.

It’s not about what is, it’s about what we think it is. And that’s where perception becomes powerful-or dangerous.

Seeing Beyond Self

Perspective is stepping outside your emotional reaction and choosing to see a bigger truth. It’s the ability to view the moment from someone else’s angle—or even from your future self’s. It’s not something that happens to you. It’s something you choose to do.

In rugby, as a Scrumhalf, I had to make fast reads and act instinctively. But instinct can betray you when it’s fueled by emotion or assumption. I remember times I thought the Flyhalf wasn’t listening or the forward pack wasn’t working hard enough. That was my perception. But from the Fullback’s view—who could see the fatigue setting in across the front line or the defensive pressure building up wide—things looked very different. He’d call out adjustments not based on emotion but on the whole field. That’s perspective.

Perspective isn’t just seeing more—it’s feeling less threatened by what you see. It’s the ability to pause and ask:“Is this really about me, or is there a bigger picture I’m missing?”

In cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), this is called cognitive reframing: the skill of interpreting events through a more balanced, external lens (Beck, 2011). It’s one of the most effective tools for regulating emotion, building resilience, and making better decisions under pressure. Elite performers train this—not because they don’t feel things, but because they can’t afford to be ruled by perception.

Faith-based coaching ties this shift into spiritual maturity. Romans 12:2 encourages us to “be transformed by the renewing of your mind.” That renewal? That’s perspective. That’s getting your eyes off the ruck and into the wider field. It’s not reactive—it’s intentional. It’s trained. And it’s powerful.

In rugby, as a Scrumhalf, I had to make fast reads and act instinctively. But instinct can betray you when it’s fueled by emotion or assumption. I remember times I thought the Flyhalf wasn’t listening or the forward pack wasn’t working hard enough. That was my perception. But from the Fullback’s view—who could see the fatigue setting in across the front line or the defensive pressure building up wide—things looked very different. He’d call out adjustments not based on emotion but on the whole field. That’s perspective.

Perspective isn’t just seeing more—it’s feeling less threatened by what you see. It’s the ability to pause and ask:“Is this really about me, or is there a bigger picture I’m missing?”

In cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), this is called cognitive reframing: the skill of interpreting events through a more balanced, external lens (Beck, 2011). It’s one of the most effective tools for regulating emotion, building resilience, and making better decisions under pressure. Elite performers train this—not because they don’t feel things, but because they can’t afford to be ruled by perception.

Faith-based coaching ties this shift into spiritual maturity. Romans 12:2 encourages us to “be transformed by the renewing of your mind.” That renewal? That’s perspective. That’s getting your eyes off the ruck and into the wider field. It’s not reactive—it’s intentional. It’s trained. And it’s powerful.

Perspective is a Competitive Advantage

When I coach athletes, I often remind them: the difference between losing your cool and leveling up isn’t about talent—it’s about how you see what’s happening in front of you. That difference? It’s the mental skill of perspective. And it’s not just a coaching catchphrase. It’s science.

Researchers call it self-distancing—the ability to step outside your emotions and look at a moment from a third-person view. Think of it like a mental camera drone. Instead of reacting from the heat of the ruck, you fly above the field. You see the patterns. You notice the gaps. Kross and Ayduk (2011) found that athletes who practice this kind of thinking perform better, manage emotions more effectively, and bounce back quicker. It’s exactly what Fullbacks do instinctively on the field—and what elite performers train off the field.

Another powerful tool is what psychology calls cognitive reappraisal—the ability to reframe what something means. Gross and John (2003) showed that individuals who do this consistently are more resilient and focused. In real time, this looks like an athlete interpreting butterflies as energy, not fear. Or a coach turning a tough loss into a lesson, not a label.

And then there’s mindfulness—the kind that doesn’t mean silence and candles, but awareness and pause. Josefsson and colleagues (2017) discovered that mindfulness enhances an athlete’s emotional regulation and reduces the tendency to ruminate. It creates the space for perspective to enter—especially in pressure moments.

Lastly, one of the oldest truths in high performance psychology: the story you tell yourself matters. According to Weiner’s attribution theory (1985), when athletes take ownership of their performance and view outcomes through a lens of personal growth and controllable effort, they’re more likely to succeed long term. Perspective doesn’t just shape how you interpret a moment—it shapes your future.

All of this points to one thing: zooming out—mentally, emotionally, and spiritually—isn’t just a coping skill.

It’s a competitive edge.

Researchers call it self-distancing—the ability to step outside your emotions and look at a moment from a third-person view. Think of it like a mental camera drone. Instead of reacting from the heat of the ruck, you fly above the field. You see the patterns. You notice the gaps. Kross and Ayduk (2011) found that athletes who practice this kind of thinking perform better, manage emotions more effectively, and bounce back quicker. It’s exactly what Fullbacks do instinctively on the field—and what elite performers train off the field.

Another powerful tool is what psychology calls cognitive reappraisal—the ability to reframe what something means. Gross and John (2003) showed that individuals who do this consistently are more resilient and focused. In real time, this looks like an athlete interpreting butterflies as energy, not fear. Or a coach turning a tough loss into a lesson, not a label.

And then there’s mindfulness—the kind that doesn’t mean silence and candles, but awareness and pause. Josefsson and colleagues (2017) discovered that mindfulness enhances an athlete’s emotional regulation and reduces the tendency to ruminate. It creates the space for perspective to enter—especially in pressure moments.

Lastly, one of the oldest truths in high performance psychology: the story you tell yourself matters. According to Weiner’s attribution theory (1985), when athletes take ownership of their performance and view outcomes through a lens of personal growth and controllable effort, they’re more likely to succeed long term. Perspective doesn’t just shape how you interpret a moment—it shapes your future.

All of this points to one thing: zooming out—mentally, emotionally, and spiritually—isn’t just a coping skill.

It’s a competitive edge.

Apply the Wisdom

Let’s take this off the page and into real life—into the minds of athletes, coaches, and parents.

For the athlete, perception shows up fast. You get benched, and suddenly a wave of thoughts hits: “I must not be good enough.” Your chest tightens. Your confidence slips. You start doubting your place on the team, your value, even your future. That’s perception—raw, emotional, immediate. It’s the Scrumhalf’s view—right in the thick of the ruck, eyes fixed on what’s two feet in front of you.

But then there’s perspective. It says: “What’s my coach seeing? What’s the pace of the game? What have I shown in practice that I can improve?” It allows you to consider timing, strategy, growth—all the elements that don’t scream at you in the heat of the moment. Perspective doesn’t soften the sting, but it gives the sting a purpose.

For the coach, perception can be just as reactive. A player walks into practice with slumped shoulders, barely makes eye contact, and doesn’t respond to a correction. Perception says, “They don’t care. They’re being disrespectful.” You tighten up. You coach harder, maybe louder. You react to the story you’ve told yourself.

But perspective pauses long enough to ask: “Is something going on at home? Is this pressure? Is this fatigue?” Perspective recognizes that leadership isn’t about control—it’s about understanding. It sees behavior not just as performance, but as communication.

And for the parent—maybe the most emotionally charged role of all—perception is often tangled up with protection. Your child comes home frustrated after a game, eyes low, voice sharp. You feel your own heart rise. “That coach isn’t treating my kid fairly.” Or “They’re losing confidence—I need to fix this.”

But perspective reminds you that growth often looks like discomfort. That confidence is forged, not given. It invites you to ask better questions:

“What did you learn?”

“What was the hardest part?”

“What can we work on together?”

Perspective doesn’t ignore the emotion—it just refuses to let emotion drive the story.

In all three roles, the challenge is the same: to step back before you step in. Because when you lead from perspective, you don’t just change your response—you change the outcome. You build athletes who can regulate, coaches who can connect, and parents who can lead with wisdom instead of fear.

This is what the Fullbacks of the world do well. They still feel the game. But they see it, too.

For the athlete, perception shows up fast. You get benched, and suddenly a wave of thoughts hits: “I must not be good enough.” Your chest tightens. Your confidence slips. You start doubting your place on the team, your value, even your future. That’s perception—raw, emotional, immediate. It’s the Scrumhalf’s view—right in the thick of the ruck, eyes fixed on what’s two feet in front of you.

But then there’s perspective. It says: “What’s my coach seeing? What’s the pace of the game? What have I shown in practice that I can improve?” It allows you to consider timing, strategy, growth—all the elements that don’t scream at you in the heat of the moment. Perspective doesn’t soften the sting, but it gives the sting a purpose.

For the coach, perception can be just as reactive. A player walks into practice with slumped shoulders, barely makes eye contact, and doesn’t respond to a correction. Perception says, “They don’t care. They’re being disrespectful.” You tighten up. You coach harder, maybe louder. You react to the story you’ve told yourself.

But perspective pauses long enough to ask: “Is something going on at home? Is this pressure? Is this fatigue?” Perspective recognizes that leadership isn’t about control—it’s about understanding. It sees behavior not just as performance, but as communication.

And for the parent—maybe the most emotionally charged role of all—perception is often tangled up with protection. Your child comes home frustrated after a game, eyes low, voice sharp. You feel your own heart rise. “That coach isn’t treating my kid fairly.” Or “They’re losing confidence—I need to fix this.”

But perspective reminds you that growth often looks like discomfort. That confidence is forged, not given. It invites you to ask better questions:

“What did you learn?”

“What was the hardest part?”

“What can we work on together?”

Perspective doesn’t ignore the emotion—it just refuses to let emotion drive the story.

In all three roles, the challenge is the same: to step back before you step in. Because when you lead from perspective, you don’t just change your response—you change the outcome. You build athletes who can regulate, coaches who can connect, and parents who can lead with wisdom instead of fear.

This is what the Fullbacks of the world do well. They still feel the game. But they see it, too.

Learning to Step Back Before You Step In

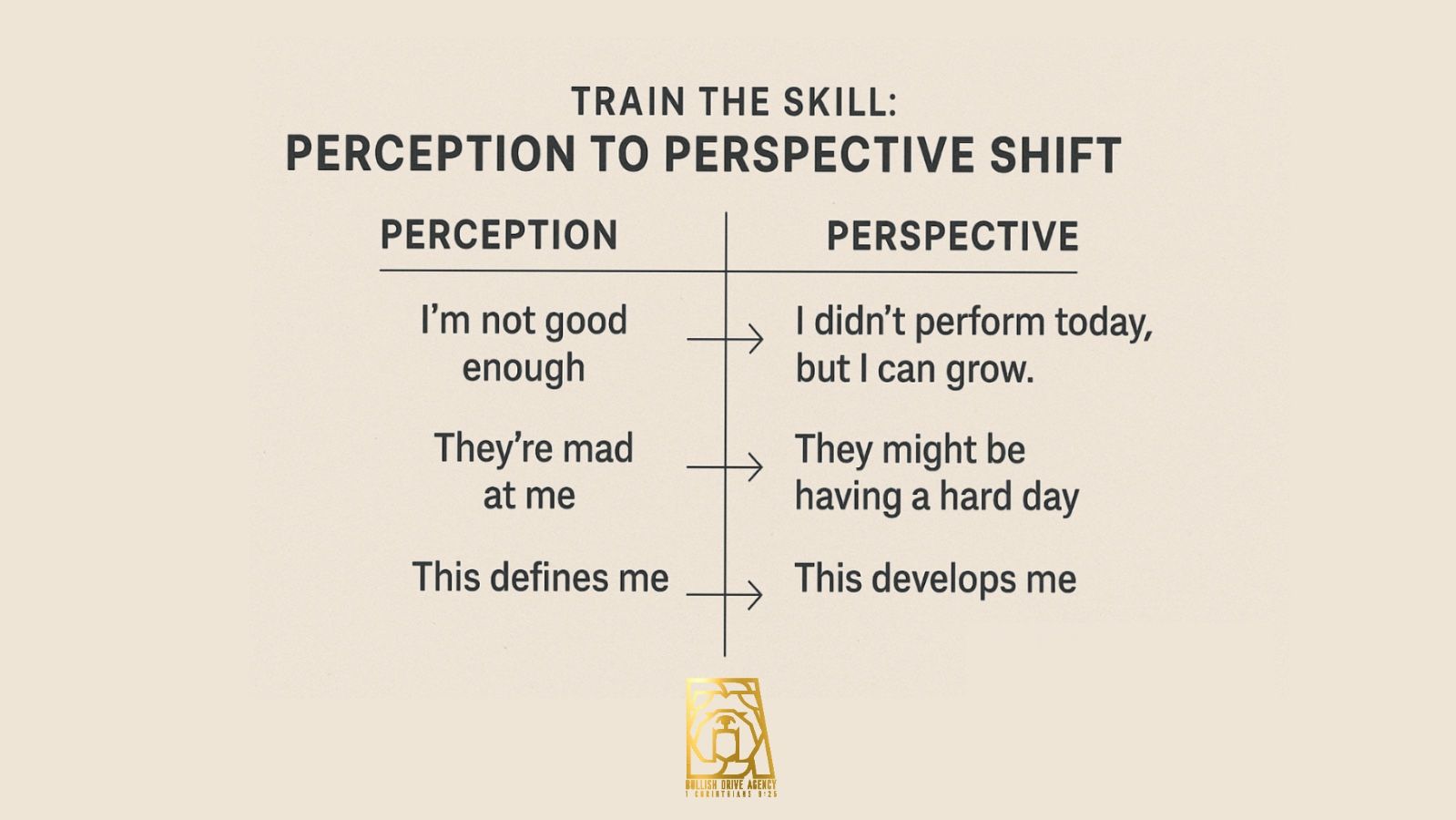

Perspective isn’t a gift—it’s a skill. It doesn’t just show up when life gets hard or when performance is on the line. Like anything else in athletics or life, it has to be trained.

The athletes I work with often ask, “How do I stop overthinking?” or “How do I not let one mistake ruin the rest of the game?” And my response is always the same:

“You don’t wait for the storm to practice calm.”

You prepare for pressure before pressure hits.

Perspective is trained in the small moments, the daily reps. It starts with awareness.

Let’s say you’re walking off the court or field, head spinning from a bad performance. The old you—driven by perception—might spiral. Replay every mistake. Make assumptions. Blame. Shut down.

But here’s where you insert the rep:

Take a breath.

Ask yourself: “What else could be true here?”

It’s a simple question, but it cracks open the door to wisdom. Instead of just reacting, you begin reflecting. Instead of judgment, you lean into curiosity.

Another rep: use mental time-travel. When a moment feels overwhelming, ask:

“Will this still matter in 3 days? In 3 years?”

This stretches your thinking beyond the now and gives weight only to what truly deserves it. It’s like zooming the camera lens out—just like that Fullback surveying the whole field instead of chasing every pass.

Perspective is also built through journaling. Write down what you felt in the moment—and then revisit it a day later. Ask yourself:

What was real?

What was emotional?

What changed after time and space?

You’ll begin to see a pattern: emotions distort facts. But time and reflection can realign them.

For those who lead from faith, perspective training deepens even more. Scripture becomes an anchor. Philippians 4:8 gives a filter for your focus—whatever is true, noble, right, pure, and praiseworthy, think on these things. It’s not about ignoring hardship, but about choosing what lens to carry through it.

And finally, a practical drill I give my athletes:

Coach yourself.

If a teammate came to you with the exact situation you’re in—what would you say to them? Now say it to yourself. That’s self-compassion and perspective working together.

You don’t have to be perfect at this. You just have to practice it.

Every breath.

Every pause.

Every moment you choose to respond instead of react, you’re training something far more valuable than muscle—you’re training mental vision.

The athletes I work with often ask, “How do I stop overthinking?” or “How do I not let one mistake ruin the rest of the game?” And my response is always the same:

“You don’t wait for the storm to practice calm.”

You prepare for pressure before pressure hits.

Perspective is trained in the small moments, the daily reps. It starts with awareness.

Let’s say you’re walking off the court or field, head spinning from a bad performance. The old you—driven by perception—might spiral. Replay every mistake. Make assumptions. Blame. Shut down.

But here’s where you insert the rep:

Take a breath.

Ask yourself: “What else could be true here?”

It’s a simple question, but it cracks open the door to wisdom. Instead of just reacting, you begin reflecting. Instead of judgment, you lean into curiosity.

Another rep: use mental time-travel. When a moment feels overwhelming, ask:

“Will this still matter in 3 days? In 3 years?”

This stretches your thinking beyond the now and gives weight only to what truly deserves it. It’s like zooming the camera lens out—just like that Fullback surveying the whole field instead of chasing every pass.

Perspective is also built through journaling. Write down what you felt in the moment—and then revisit it a day later. Ask yourself:

What was real?

What was emotional?

What changed after time and space?

You’ll begin to see a pattern: emotions distort facts. But time and reflection can realign them.

For those who lead from faith, perspective training deepens even more. Scripture becomes an anchor. Philippians 4:8 gives a filter for your focus—whatever is true, noble, right, pure, and praiseworthy, think on these things. It’s not about ignoring hardship, but about choosing what lens to carry through it.

And finally, a practical drill I give my athletes:

Coach yourself.

If a teammate came to you with the exact situation you’re in—what would you say to them? Now say it to yourself. That’s self-compassion and perspective working together.

You don’t have to be perfect at this. You just have to practice it.

Every breath.

Every pause.

Every moment you choose to respond instead of react, you’re training something far more valuable than muscle—you’re training mental vision.

Seeing the Field Differently

Let’s go back to the field.

As a Scrumhalf, I had to be in the action. Every ruck, every pass, every decision lived in the now. That was necessary. But it was also limiting. I only saw what was right in front of me.

The Fullback though—he saw everything. He wasn’t caught in the chaos; he was reading it. He saw the open space, the imbalances, the opportunities no one else could see. His calls changed the way we played. Not because he worked harder, but because he saw wider.

That’s the power of perspective.

In life, in sport, and in leadership—there are moments where your perception will scream the loudest. Moments when emotion will beg to take control. But if you can train yourself to step back, to zoom out, to see beyond just you—you’ll lead better. You’ll recover faster. You’ll make decisions rooted in wisdom, not wounds.

So here’s the challenge:

Where in your life are you stuck in perception?

And what would it look like to shift into perspective?

Whether you’re an athlete trying to win the next point, a coach trying to reach a player, or a parent trying to guide your child—remember this:

You can’t always control what you see.

But you can always choose how you see it.

As a Scrumhalf, I had to be in the action. Every ruck, every pass, every decision lived in the now. That was necessary. But it was also limiting. I only saw what was right in front of me.

The Fullback though—he saw everything. He wasn’t caught in the chaos; he was reading it. He saw the open space, the imbalances, the opportunities no one else could see. His calls changed the way we played. Not because he worked harder, but because he saw wider.

That’s the power of perspective.

In life, in sport, and in leadership—there are moments where your perception will scream the loudest. Moments when emotion will beg to take control. But if you can train yourself to step back, to zoom out, to see beyond just you—you’ll lead better. You’ll recover faster. You’ll make decisions rooted in wisdom, not wounds.

So here’s the challenge:

Where in your life are you stuck in perception?

And what would it look like to shift into perspective?

Whether you’re an athlete trying to win the next point, a coach trying to reach a player, or a parent trying to guide your child—remember this:

You can’t always control what you see.

But you can always choose how you see it.

References

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362.

Josefsson, T., Ivarsson, A., Gustafsson, H., & Stenling, A. (2017). Mindfulness mechanisms in sports: Mediating effects of rumination and emotion regulation on sport-specific coping. Mindfulness, 8(5), 1354–1363.

Kross, E., & Ayduk, O. (2011). Making meaning out of negative experiences by self-distancing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 187–191.

Moen, F. (2016). Coaching leadership and cognitive reappraisal: An experimental study. Journal of Coaching Education, 9(1), 30–44.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362.

Josefsson, T., Ivarsson, A., Gustafsson, H., & Stenling, A. (2017). Mindfulness mechanisms in sports: Mediating effects of rumination and emotion regulation on sport-specific coping. Mindfulness, 8(5), 1354–1363.

Kross, E., & Ayduk, O. (2011). Making meaning out of negative experiences by self-distancing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 187–191.

Moen, F. (2016). Coaching leadership and cognitive reappraisal: An experimental study. Journal of Coaching Education, 9(1), 30–44.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573.

Written By

James Driessen